Story by: Joanne Musau, Citizen Journalist

When Rose*, a community leader representing People Living with HIV (PLHIV) in Marsabit, sent a desperate message to a WhatsApp support group last week, it carried devastating news that one of their members had died and not from HIV, but from hunger. “We have lost one of our members to hunger. Others are admitted to the hospital, too weak to fend for themselves. They can only hope someone will step in to save them,” she wrote.

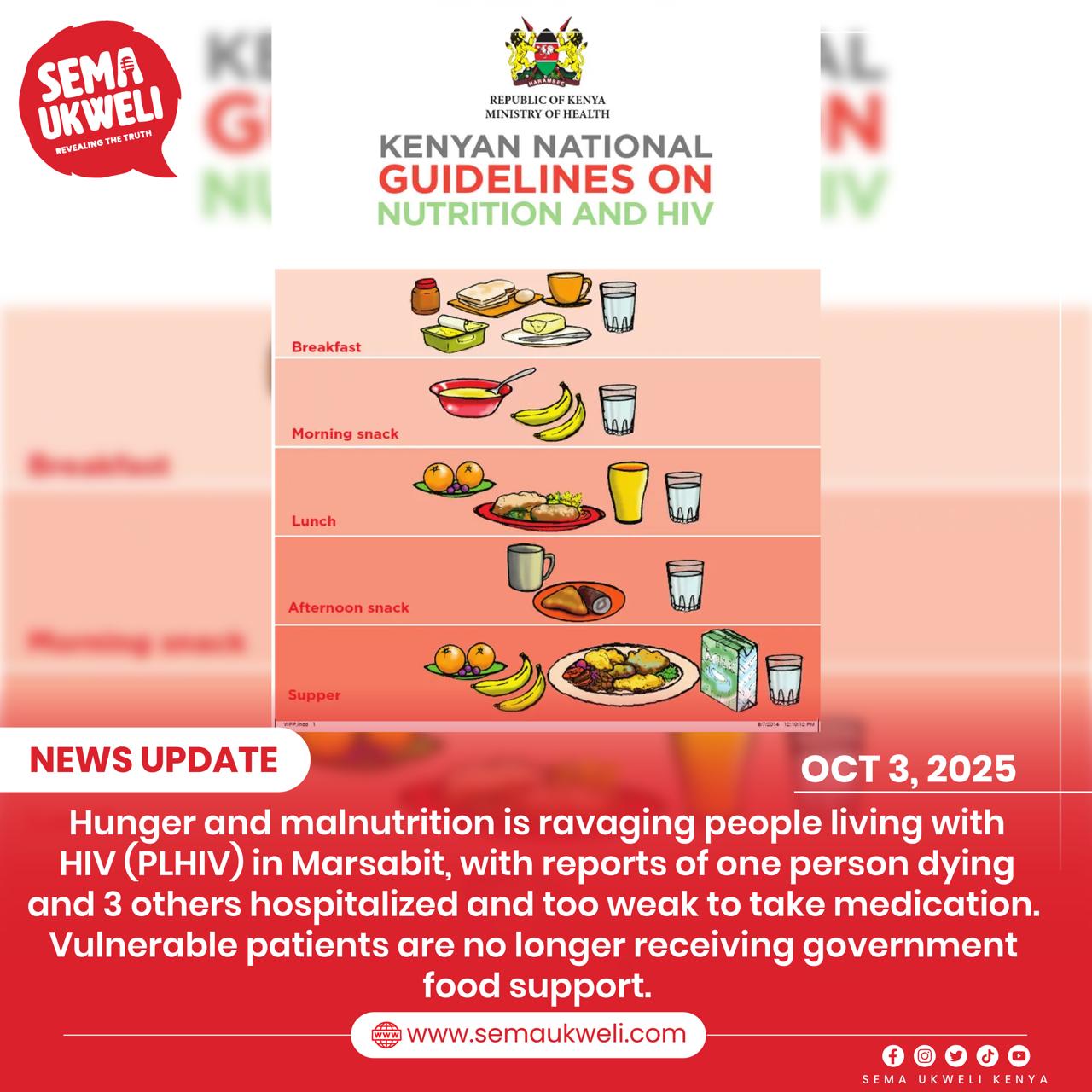

The deceased had been on both tuberculosis and HIV treatment. Without food, the life-saving drugs became intolerable. At least three other PLHIV are admitted to the hospital in similar conditions. For Rose and many others, the challenge is not access to medication but the food required to take it safely. “Taking ARVs on an empty stomach is like swallowing poison into your body as it tends to burn and destroy the organs,” she explained.

The WhatsApp group Rose belongs to is run by the National Empowerment Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Kenya (NEPHAK). It has become a lifeline for sharing updates and emergency fundraising. But for months now, members have watched their situation worsen as food donations they once received from the District Commissioner’s office dried up.

“We feel abandoned. Several lactating mothers are breastfeeding on an empty stomach, their bodies too weak to provide nourishment. They have children looking up to them, but how do you care for a family when you are weak?” Rose asked.

Health experts warn that delaying or skipping doses of antiretroviral (ARV) medication because of hunger is dangerous. ARVs cannot be taken on an empty stomach without severe side effects. Poor adherence weakens immunity, increases the risk of opportunistic infections, and increases the likelihood of death.

“Early management of malnutrition is a key action to reduce mortality among PLHIV,” explained NEPHAK Chief Executive Officer Nelson Otwoma. According to him, the network’s leadership and county-based members have been sending small contributions, as little as KSh200 each, to support food purchases in Marsabit. “It is not enough, but it is something. We wish that the county and national response teams and well-wishers could step in with more support,” Otwoma added.

The loss of food support has raised questions about leadership and responsibility. “Where is the county relief team? Where are the leaders these same people elected to power?” asked Otwoma. “Are PLHIV only important during voting season?”

The loss of food support has raised questions about leadership and responsibility at the county level. But even beyond Marsabit, broader shifts in global health financing are undermining Kenya’s HIV response, adding new layers of strain to an already fragile system.

Shifts in global health financing have further complicated Kenya’s situation. The Global Fund has reduced Kenya’s allocation by nearly KSh 7 billion in 2025, while foreign aid through programmes like the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has also been affected or frozen. These combined pressures are raising concerns about potential disruptions in ARV supply chains and diagnostic services in parts of the health system.

Otwoma says sustainable solutions are required, with NEPHAK calling for support groups to be trained in income-generating activities that can improve household nutrition and reduce overreliance on relief. “We believe these communities can withstand hunger shocks with the right economic empowerment projects,” he said. However, for Rose and her peers, survival is no longer just about managing HIV but about finding the next meal.

*Name changed to protect identity